An Online Reflection of Cuba

Havana coastline photo: Caridad

HAVANA TIMES — I was sitting with a group of friends (students and teachers) on the grass at the former Institute of Sciences and Nuclear Technologies (today INSTEC), at Havana’s old “Finca de los Molinos” estate.” This was at the end of 2008.

Out of the blue, one of the guys there remarked, “I’m writing for the website of an American who lives in Cuba.” I remembered reeling back dumfounded by that contradictory comment: An American? in Cuba? The words immediately brought to my mind a conspiratorial backdrop that smacked of geopolitical confrontation, espionage and ideologies hopelessly at odds.

“This American works at ESTI (the Cuban translation agency),” he explained. “The website began not very long ago. The guy’s pulling together a team where each person will write a blog.” That made it both clearer and stranger at the same time. To cap it off, he added, “The group of bloggers should have the same number of men as women. A gender balance thing.”

The name Circles Robinson isn’t very well known in Cuba, but he’s the editor of one of the most popular online news sites on Cuba that has hit the web. It’s the burgeoning Havana Times online publication, administered today from another ALBA country (Nicaragua). These writings are reaching an ever wider audience in Cuba, by on-line connection for the few or by e-mail for the rest.

It is an online medium where diaries of ordinary Cubans coexist with rigorous reports from correspondents with the Cuban-accredited Inter Press Service agency (IPS), as well as with analytical articles and the opinions of recognized experts; it also publishes interviews and excellent photographs.

Sharing a Deeper Look at Cuba

This project of Circles Robinson succeeds, perhaps without intending to, in sharing with non-Cubans an in-depth vision of Cuba: our “Cuba profunda.” When we walk down the street or look out our windows, we’re usually able to perceive the countless details that served as inspiration for people like Don Fernando, Lezama, Dulce Maria, Oscar Hurtado or Victor Fowler in their multiple inquiries about the experiential spirituality of our country.

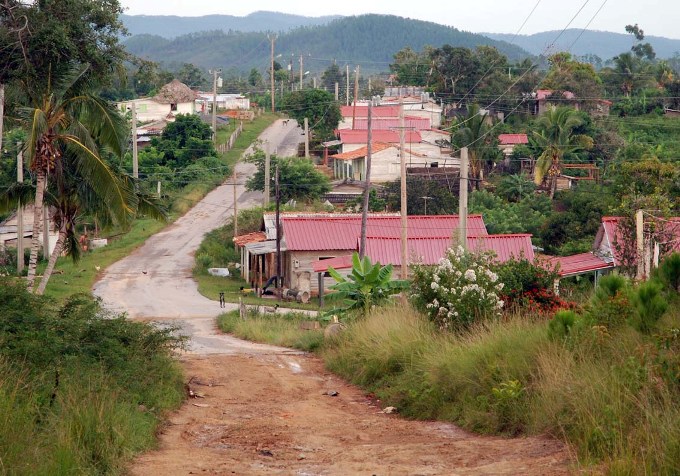

Viñales, Pinar del Rio. Photo: Caridad

And what can one say about the symbols that fill our minds? For me, the exceptional merit of Havana Times is that it allows people from other countries to share in the signs and symbols of current “Cubania” without these being denigrated as “folkloric” or converted into “pasto para turistas” (tourist fodder).

Clearly this is only the personal opinion of a regular contributor to the publication, but I can bear witness: my own perception of “me and my circumstances” in Cuba has been attaining greater clarity since I began writing for the site. Through writings and photographs, Havana Times graphically reveals a Cuba that is neither hell nor heaven, though certainly a place where it’s possible to live and share one’s life.

It’s an Internet site whose main characters are, for the most part, people “like everybody else”: workers, students, self-employed, professionals, artists and writers. The Havana Times collective is like a family. Its subtitle in English, “Open-minded writing from Cuba,” means just that. Having an open mind is to distance oneself from the same old boring monotones that have been so justly criticized, as well as from tiresome polarized aggressiveness… It’s an invitation to dialogue in a Cuba where many Cubas fit.

A palpably uncomfortable journalism

Despite this, the site has never tried to duck controversy. In a recent polemical post, a leftist blogger (from the group “Bloggers Cuba”) compared Robinson to none less than Charles Dana, the editor of the New York newspaper that published Marx and Marti. Perhaps it’s an exaggerated praise, but let’s remember too that bloggers suspicious of anyone who promotes questioning and divergent thinking abound on the Cuban web.

Havana Times is a formidable source of information and debate that has covered subjects ranging from a (failed) expedition to the biggest garbage dump in the Cuban capital, to incidents related to a professor who lost his job in a conflict with the administration, the complex problems of transgenic crop cultivation, domestic violence and the life of the imprisoned “Cuban Five” in the United States.

It is a type of journalism that’s uncomfortable for many, generated by people who for the most part are not trained as journalists (and among these “amateurs,” by the way, is the editor himself).

However, speaking of “uncomfortable journalism” – isn’t that what many of us want, for the good of Cuba? Because of that, Havana Times has started to become a part of Cuban reality, part of the complex processes of change that are now occurring. It’s one of those X rays machines with which our society — finally! — can look at its insides.

Filled with a desire to unravel the “intrigue” shrouding the subject in question (“Who is Circles Robinson?”), I requested an interview from him, aware of how controversial this would be. Circles, who is already a friend of many of us, kindly agreed to allow me to share this dialogue in the pages of Espacio Laical, a publication of the Catholic Church of Cuba. At this point, we’ll ask him to speak in his own words:

Who is Circles Robinson and how did you come to live in Cuba? What was your occupation on the island before starting up Havana Times?

Generations ago my family were immigrants to the United States from Rumania and Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, and I was born and raised in Los Angeles. However the formative experiences of my life took place very distant from that atmosphere: in a small town in the old US West and in Latin America, where I’ve spent most of my adult life.

Since 1982 I’ve lived outside of my country — in Spain, Nicaragua and Cuba — working in everything from agriculture, cooperatives and tourism, to international relations and translation, but with a recurrent link to journalism and small publications.

My interest in Latin America began when I left the US for the first time, in 1972, dodging the military draft during the Vietnam War. In Colombia, where I lived for two years, I became somewhat aware of the effect of US policy on the continent. This culminated with my sensing — albeit from a distance — the repercussions of the military coup in Chile against Allende on September 11, 1973.

I also experienced the Colombian people’s warmth, the value they placed on family, their stories and mysteries, and the food. From all this came my preference for living in Latin America.

Ultimately I won in the draft lottery, a sort of sinister Bingo-like drawing that the US Army employed for recruiting youths into its war machine. At that time the service was obligatory, but some of the men would never have to serve due to their numbers in the lottery being too high. I was one of them, so I could return to the United States, which I did in 1974, without having to wait for the amnesty given by Carter in 1977.

I went to live in a small town, Bisbee, Arizona, previously a copper mining town on the Mexican border. There I worked for the local radio station, published a newspaper, learned a little something about typography and managed a small food cooperative. Local political activism (and some degree of solidarity with the FMLN in El Salvador and the FSLN in Nicaragua) characterized my years in this town as part of a group that sought a “better world,” though on a smaller scale.

After leaving the US permanently in 1982, I first lived to the south of Granada, Spain, working in agriculture and participating in a small cooperative.

At the end of ‘84, in the face of threats by recently re-elected president Ronald Reagan to invade Nicaragua, I decided to contribute my grain of sand working in coffee plantations in that country, also as a way to understand the Nicaraguan Revolution. I picked coffee with a large brigade of “nica” teachers and another smaller contingent from a Nicaraguan Christian base community.

After 17 years in Nicaragua, experiencing the revolution and its subsequent debacle (1990), I went to live in Cuba at the end of 2001. I was hired by the Prensa Latina news agency as a translator/reviser of their English service. From the beginning I established lots of contacts with the journalists and I concerned myself with trying to make the materials that I revised communicate a little more, a little better, to the readers abroad.

Along with my wife, daughter and grandson, I lived in Tarara (on the far eastside of Havana) because this was where PL offered housing for its technicians at that time. It was a beautiful place right off the beach, but it was also far from the city and that meant hours of daily waiting for buses or hitchhiking.

At that time my wife worked as a volunteer for two “Transformation Workshops” (Spanish: Talleres de Transformacion) in the Havana neighborhoods of Atares and El Canal. My daughter studied for a year at the National Art School (ENA) before beginning her studies (paid for by us) at the faculty of Audiovisual

Media at the Superior Institute of Art (ISA). My little grandson began his first daycare center once he learned how to walk, a month after arriving in Cuba. As a result of all this, I had the opportunity to become aware of Cuban life from several perspectives.

In mid-2004 I accepted an offer to work in the same capacity for other Cuban online media, but from a new office called On-line Translation based out of the national translation/interpretation office (ESTI). My family’s housing situation was decisive in that decision. As such, we moved into an apartment recently vacated by another foreign translator. It was located in Miramar near the Karl Marx Theater, and half a block from my daughter’s university campus.

At ESTI, given our involvement with the Cuban press, the small staff that worked for On-line Translation formed a chapter of the “Cuban Journalists Association” (UPEC). I also began to write a personal blog at the end of 2005, partly in response to a suggestion from UPEC to its members.

In the following years I participated in the training of translators and webmasters on how to improve their pages in English. I drafted a report and presented it in meetings convened by the PCC for the staffs of digital media organizations in different provinces. As a member of UPEC and representing our chapter, I began to participate in meetings that were convened annually for journalists of the written press.

Discussions around the deficiencies in the content and scope of the Cuban press were constant among my close colleagues. In 2007 an internal directive on the media was issued from the Politburo of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC). Among other things it spoke of the need to reflect the reality of the country in news reporting – something I found highly encouraging and motivating.

I participated as a full delegate (with voting rights) in the UPEC Congress in July 2008. The topic of how to improve the press was raised there by numbers of people from the media, particularly the youth.

Nonetheless the discussions failed to produce any concrete changes, and after leaving the conference we returned to the same old thing, the same static routine – something that created only frustration for me.

Havana sunrise. Photo: Caridad

How was Havana Times created?

A little later, I decided to begin a webpage as my contribution to putting into practice the type of media that I thought — and still think — should exist for the national public and for foreign readers interested in Cuba. It was more than clear to me that the Cuban media utterly failed to reflect the country’s daily life – in the streets, on the job and in homes. Problems were practically absent, as were the rich diversity of opinions on any issue.

I felt that my personal blog had reached its end, and I wanted to do something with more reach and involving more people.

Our motto in English “Open-minded writing from Cuba” means “Cuba sin prejuicios” in Spanish. With so many media sources demonizing everything that has to do with the Cuban Revolution and its leaders on the one hand, and the monologue of the official Cuban media with its message that “everything’s almost perfect in Cuba and the rest of the world is evil,” on the other, there was a great need for a media that didn’t weigh in from either of those extremes.

I already had several experiences in the field of publishing. I had published a biweekly newspaper in the town where I lived in Arizona and years later I published a monthly magazine in English for the main farmer’s organization of Nicaragua. It was Nicaragua from a campesino perspective.

But HT was not only my idea: two other people — a Cuban and an African-American — have been indispensable parts of the creation and continuation of the project from the beginning.

I owe a great deal of thanks to my family for the support that I’ve received in financing the project. I’ve always thought that self-financing would be the sole way to carry out the effort without making it vulnerable to criticisms of being directly or indirectly sustained by the omnipresent “enemy.” Fortunately, the costs of the initiative are modest. That’s one of the big advantages of online work.

Over a three month period we created the design, sought our initial writers and began accumulating photos. We received HT’s banner photo just a few days before going online. Start-up wasn’t easy because many of the people we approached were working for government entities or studying; and writing a for non-official Internet press entity isn’t looked upon very well by many supervisors, professors and party functionaries.

We opted for a simple but attractive design, with lots of photos – that’s one of the strengths of HT. In the beginning the publication only came out in English, focusing on non-Spanish-speaking readers interested in Cuba, be it for tourism, study or whatever. This was consistent with my job as a foreign technician working for the online English language media in Cuba.

Among the goals was to present different situations experienced in the country and the wide diversity of opinions, showing the beauty and achievements as well as the blemishes and real problems. In short, we were aiming to show the country in the flesh, a country like others but different at the same time.

We launched into cyberspace in mid-October of 2008, and I took on the challenge of working my regular day job with ESTI and publishing HT in my free time. It was an exhausting pace involving 14-16 hour days sitting in front of the computer. Also, though we had planned to update the page once or twice a week, the site quickly evolved into a daily online publication due to the quantity of material we received and the speed made possible by technology.

Two months after its start-up we officially presented the site at the UPEC headquarters before the directors of that organization and representatives of a number of Cuban media.

Tell us how your previous experiences influenced the concept and style of your new online magazine?

There were many Cubans who experienced the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist camp first hand while studying or undergoing training in those countries. I myself didn’t experience Eastern Europe first hand, but I did witness the painful collapse of the revolution in Nicaragua. It was like seeing the closing of a great window of opportunity — for creativity and for learning from other efforts, for improving — all shut in a single motion. I still feel the pain even today.

For me the Nicaraguan Revolution was like Cuba’s, another David vs. Goliath story with great freshness and hope, but which gradually began to extinguish.

The economic blockade that Nicaragua suffered, like Cuba, and the war (also sponsored by the US) played a significant role. However for me the reversal was due to the loss of revolutionary ethics, self-adulation by the senior leadership, a triumphalist monologue, the lack of controls and economic mismanagement, the lack of substantive participation by the people in decision making, plus the gradual distancing of the leadership from the base and their believing themselves to be eternally in power, all of which led to the crushing electoral debacle of February 25, 1990.

After the hurricanes. Photo: Caridad

After that disaster I stayed, working seven more years for the campesino organization UNAG, the counterpart to Cuba’s ANAP and which included the cooperative movement. During that time I, like many other people, tried to figure out what had happened, still dreaming of another chance to transform the world into something different…where people, social justice, collective well-being and nature were more important than capital, and where people would reflect on their errors instead of repeating them.

Going to Cuba a decade later was an opportunity for me to see how it might have been if Nicaragua’s revolution has lasted 40 years instead of just 10… what would have been its achievements, its strengths as well as its problems and weak points? Nicaragua was not a copy of Cuba but it was influenced by its big brother in many aspects.

By living in Cuba I realized how much the Nicaraguan Revolution meant to Cubans at a personal level, for each individual. What had happened was very painful for them too.

With respect to the media, I remember that Salman Rushdie in his book on Nicaragua (The Jaguar Smile) wrote that the Sandinista party’s newspaper (Barricada) was the worst he’d ever seen.

At that time — finding myself in the middle of the war and accepting the leaders’ arguments concerning the need to restrict information and criticism for the sake of unity — I didn’t agree with anything Rushdie said. Later I did come to concur with him. It was in fact a terrible newspaper that minimized the capacity of people to assess information and to reach their own conclusions.

In Cuba I found a fascinating country with major achievements as a society but one with enormous cumulative problems. The investment that had been made over half a century to promote culture was evident, and being in the capital I was able to enjoy the fruits of those advances.

Collectively, the press, radio and TV were something altogether different though. It was a return to the Barricada. What I found in the Cuban media was that same monologue: asserting possession of the absolute truth while omitting information, misusing statistics and claiming a false unity, not to mention the constant stream of triumphalism. In short, what current president Raul Castro describes as “the boring press.”

We wanted to do something different with HT, something where ordinary people had a voice, not only leaders and recognized intellectuals. We also intended to include the work of experienced journalists and photographers along with reports and commentaries.

The goal has been to reflect the range of realities and challenges faced in the country. Hence, our “diaries” section was born. In this section are the personal logs of our bloggers, who come from a wide variety of fields and have an equally broad range of opinions and beliefs/ideologies.

How is Havana Times different from other similar media? And what do they share?

I don’t think there’s really anything similar with the great majority of the young writers living in Cuba. Perhaps the closest things in format are Cubaencuentro and Diario de Cuba. Although technically we’re just one more of the thousand-plus websites written about Cuba, we opted from the beginning for a format that was more like an online newspaper, and this has worked for us.

At one single site we have the voices of 15 people writing their blogs in the first person; in addition there are reports, commentaries and photo features by veterans as well as novices to the trade. We also reproduce materials from the IPS news agency, which has racked up more than 30 years of reporting from Cuba.

Photo by Caridad.

With respect to the content, I believe that several elements distinguish us: the diversity of opinions and styles, ranging from intellectual analyses to very simple and direct styles; our not being rigid extremists and not being the mouthpiece of any party, organization, institution or movement.

We cover and comment on issues concerning the economy as well as sports, culture etc. It’s simply a publication that looks for ways to elevate the knowledge about and interest in Cuba and attempts to be accessible to a board spectrum of national and foreign readers.

Is there any contradiction between your previous occupations and the creation of this new information medium? Has your appreciation of the situation on the island changed since starting Havana Times?

On the contrary, having translated and revised for the Cuban media for seven years gave me many ideas about how journalism here could move forward over time. Translating and revising journalistic materials can be extremely boring when the materials are of little interest, repetitive, missing information and are oblivious to what the most casual observer can see all around. But it also gives you a lot to think about in terms of how you would write, including your topics and style.

Moreover, I had already put out other publications and ran two radio programs without being a certified professional. To succeed with HT, I drew on all my experiences. One thing I’ve learned how to do, and that I love to do, is involve more and more people, almost creating a family, and this is how it feels with the Havana Times group. We even have readers who also feel like they’re part of the project – and they are.

My appreciation of the situation concerning the Cuban media hasn’t changed. There have been timid efforts to present aspects of the different realities of the country and its people. There’s been some talk about certain problems, but it’s all been well below what’s required. Likewise, absent are focuses and opinions that diverge from official policies. They’re either nonexistent or so shy that they don’t come to mean real change. Real debate remains absent.

Furthermore, the lack of investigative journalism has done a great deal of harm to the country. I’m sure that if this type of journalism had been encouraged, rather than repressed, some of the major cases of corruption would have come to light much, much earlier. This lack of investigative reporting makes business executives and authorities feel like they’re on a throne, unquestionable and untouchable!

Who make up Havana Times?

Havana Times is a fluctuating number of 20-25 people that include writers, translators, the webmaster and me – the editor. The overwhelming majority of the group are Cubans who live on the island. They’re of all ages, though most are between 30 and 45. However we also have a couple of Cuban writers who live abroad, in addition to three US citizens, all of whom possess depths of experience after having lived in Latin America and worked for governments in countries that have undergone revolutions.

Photo: Caridad

One of the things that I insist on with those who write their diaries is the importance of their own voice, their perceptions, their experiences. This “I” exists in Havana Times, and that’s of interest to the readers. When we meet as a group every six months, we can appreciate the diversity of people who make up the collective.

The mixture of professions, jobs, abilities, backgrounds, gender, race, community activism experience and beliefs, etc. is evident. A few guests always show up at these meetings and even to them this diversity is palpable.

The writing also demonstrates this. There are people who write about personal and practical problems, while others go into philosophical matters; some deal with their neighborhoods, others touch on economic and political questions that the country is facing; then too, there are those who express concerns about social coexistence, and a few like to relate anecdotes or tackle the international terrain, etc. We only exclude those positions that use insults instead of arguments to debate.

The topics that people choose to write about come from each of them as individuals. I sometimes suggest an issue for an article or a photo feature, but this doesn’t make up more than five percent of the materials we publish.

Tell us about how the project has developed, how it has taken stands, or the surprises, conflicts and joy it has generated.

Three big changes happened the first year. The first one was our losing the support of the UPEC leadership, which was initially offered publically to Havana Times. Ultimately, after seeing the publication in practice over half a year, they couldn’t accept it as an independent and critical medium, one in which there were young non-journalists expressing themselves about their situations, their realities so distinct from the picture painted by the official media.

The second change was when my contract wasn’t renewed in June 2009. I’m convinced this action had its roots in an ethical conflict with my boss, and that Havana Times was not the principal reason. However, the net result was the loss of my temporary residency and therefore the need for my wife and I to leave the country within 30 days. I returned to Nicaragua, where I have legal residency. From there I continued the magazine with visits to Cuba every six months.

However the greatest change for HT was the September 2009 decision to put out a version in Spanish. This had been a constant request by the bloggers so that they could share their work with other Cubans.

The effect has been remarkable and growing.

The Cuban readership from the island was less than five percent the first year; now Cuba is in first place position among our Spanish readers, making up 15 percent of them. Following this are readers from Spain, the US, Mexico and Venezuela. In English, Cuba is located in fourth place behind the US, Canada and the United Kingdom. This doesn’t include the numbers of people in Cuba without Internet connections who receive HT by e-mail.

The project has demonstrated slow but steady growth. We have a modest average of around 2,000 visits to the site daily and 5,000 pages visited. This is not an insignificant amount for a relatively new publication that specializes in a single country.

Photo: Caridad

We’re building a varied readership, one of differing political perspectives, but what unites the great majority is a healthy interest or love for Cuba. They feel comfortable with the inclusive variety of opinions that are read in HT, different from what can be found in the hundreds of sites of apologetic cheerleaders or the many others set up by venomous denigrators.

So is it an effort that is primarily for “yumas” (foreigners), or is it also for Cubans? Why do you think Cubans read Havana Times? Is there some special contribution and characteristic of Havana Times when it comes to events taking place in Cuba?

I believe that Havana Times is playing a modest role in the debate on the present and future of the country and also in the analysis of its past. One of its fresh contributions is including ordinary people with their diaries or personal blogs as a fundamental part of the site.

There are intellectuals who would say that the level of writing is uneven or not at their level, but we’re not seeking to be an academic publication or one only for intellectuals. We’re cultivating the general public, which includes them if they want, but they’re not the only ones. I’d also dare say that everyone who is writing for the site has improved their skills, their ability to express themselves and their arguments.

As for the obvious question of language, we began by directing the magazine toward the Anglophone world and to Cubans who understand English, including many overseas. But now our readership is much more varied and we have increasingly more readers in different countries of Latin America, like Mexico and Venezuela.

One goal has been to remove the surprise factor for people planning to visit Cuba in the future. We put both the achievements and the problems on the table, providing certain knowledge to the readers so that when they’re in Cuba they can deepen their attempt to understand a complex and varied country. I would also say that later, many of these people will find the nuanced Cuba that they discovered in the pages of Havana Times.

For internal debate in Cuba, HT is playing a role like several other sites, providing a setting for critical expression that practically doesn’t exist in the official spaces. Obviously the big obstacle is the very limited Internet access that Cubans have, but we’ve made a beginning and the tendency is one of growth.

Havana Times has been the object of criticism from distinct political positions. How do you respond to those critics?

People with completely closed positions who believe themselves the owners of absolute truth — both those of the supposed left and those on the right — are bothered by the site and they have attacked us.

On the US side, on the right, the best example is a businessman from Massachusetts who owns more than 2,000 Internet domains with Cuba, Havana or other related keywords in their names. These were secured with the idea of promoting his present and future business activities, including sexual tourism. Since the very beginning he has maintained that I’m a “high-level agent of Cuban State Security” and that we’re “the Cuban government’s response to the famous dissident blogger Yoani Sanchez.”

At the same time, there are completely unquestioning groups of apologists in Cuba and in solidarity groups abroad who take a dim view of us. Some of them have told me that we are “playing the enemy’s game” because we publish articles exposing the many difficulties and widespread dissatisfaction in the country.

Some acquaintances and colleagues of this thought have told me that the youth who complain “should leave the country” instead of contributing criticism about the government and its policies.

Is Circles Robinson “before” Havana Times the same person as “after”?

My appreciation of life has not changed with the experience of HT though I feel a great warmth from the good friendships that have developed through the project. We have lived on the razor’s edge, ourselves being sharp hard critics but also constructive ones, hoping for understanding from Cuban officials — who can cause problems for our bloggers and even our readers in Cuba — if they don’t come to the understanding that we’re part of the process of positive change within a revolution that started 52 years ago.

I continue to hold onto the dream of being able to publish Havana Times from Cuba, like I did in the beginning. In that way I would have more contact with those contributing to the site, as well as be in closer touch with the country and even its authorities.

It might be a crazy idea on my part, but I feel that there are those even in the party who value positively our contribution to the Cuba trying to overcome this stage of immobility, stagnation and deterioration, and replace it with a new era, one of initiative, creativity, widespread participation and progress with solidarity.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home